In the case of flying lengthy distances, bats want to beat physics that forces the remainder of us mammals proper again right down to Earth.

One species’ has a trick up its membranous sleeves, new analysis reveals, permitting it to surf storm fronts for lots of of miles.

Every spring in Europe, hordes of feminine widespread noctule bats (Nyctalus noctula) wake from winter hibernation and fall pregnant with sperm that is been saved of their uteruses for months.

Carrying one or two embryos that become bat pups inside six to eight weeks, the females set out throughout the continent, homing towards the maternity colony the place they themselves had been born, typically as far north because the Baltic area.

It is a tough phenomenon for scientists to look at, and simply how they handle this long-distance trek has, till now, been a thriller.

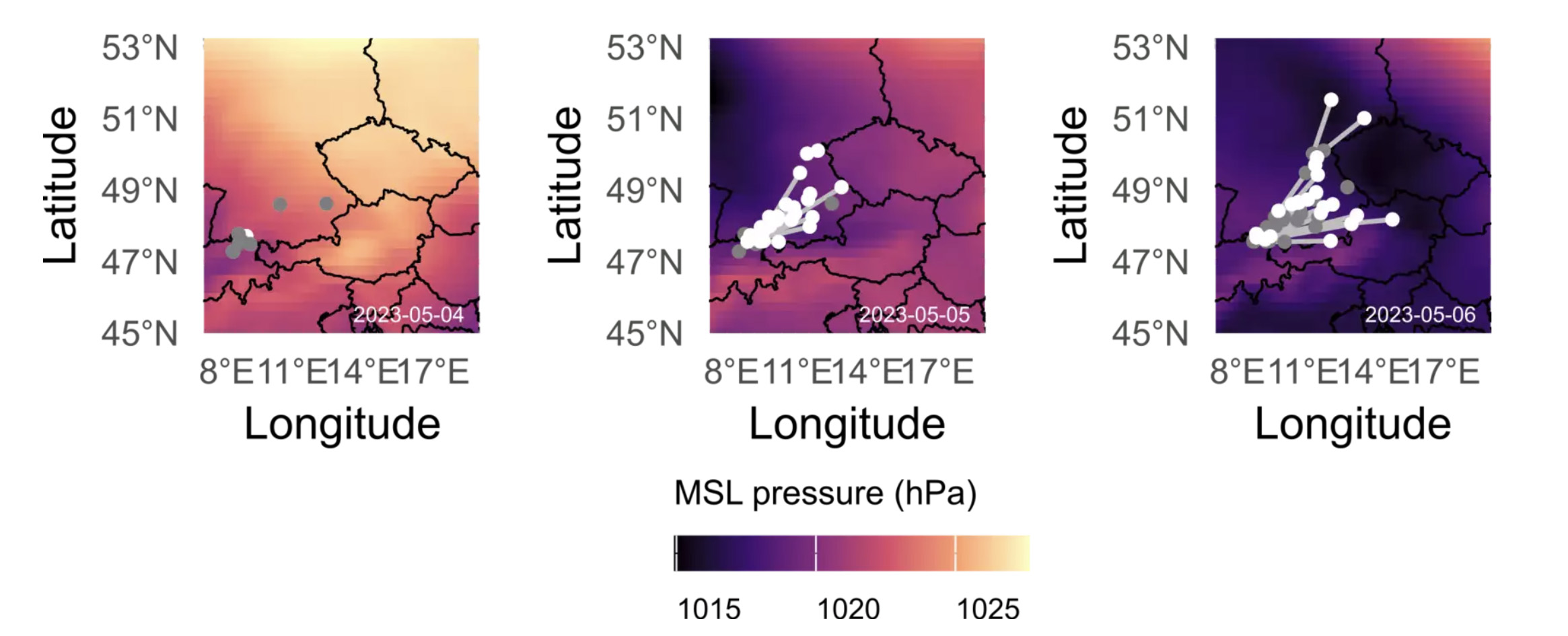

A group from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Habits in Germany glued tiny sensors onto 71 feminine noctule bats throughout their northeast migration, monitoring the animals for as much as 4 weeks and recording a powerful vary of measurements together with exercise ranges and air temperatures.

The group anticipated to see the bats stopping to refuel usually – not like migratory birds, bats do not top off fats reserves previous to their lengthy journey. However they observed an sudden sample every time the bats determined it was time to maneuver on.

“On certain nights, we saw an explosion of departures that looked like bat fireworks,” says behavioral ecologist Edward Hurme. “We needed to figure out what all these bats were responding to on those particular nights.”

Like surfers anticipating that excellent second when the wave’s curve beckons their board, the bats watch for the nice and cozy tug of air and a drop in strain that results in a spring storm.

“They were riding storm fronts, using the support of warm tailwinds,” Hurme says.

Paddling into this invisible crest, the bats hitch a experience towards their maternal roosts, overlaying astonishing distances of as much as 383 kilometers (238 miles) in a single evening.

They usually’re not simply catching one wave to get there: they’re using ‘units’ of storm fronts, nearing their vacation spot with every surge of low strain.

“There is no migration corridor,” says behavioral ecologist Dina Dechmann.

“We had assumed that bats were following a unified path, but we now see they are moving all over the landscape in a general northeast direction.”

The monitoring units confirmed the bats saved power by catching these invisible waves, an necessary issue within the equation when a child is on the way in which.

“The sensor data are amazing,” says Hurme. “We don’t just see the path that bats took, we also see what they experienced in the environment as they migrated.”

“It’s this context that gives us insight into the crucial decisions that bats made during their costly and dangerous journeys.”

This analysis was printed in Science.