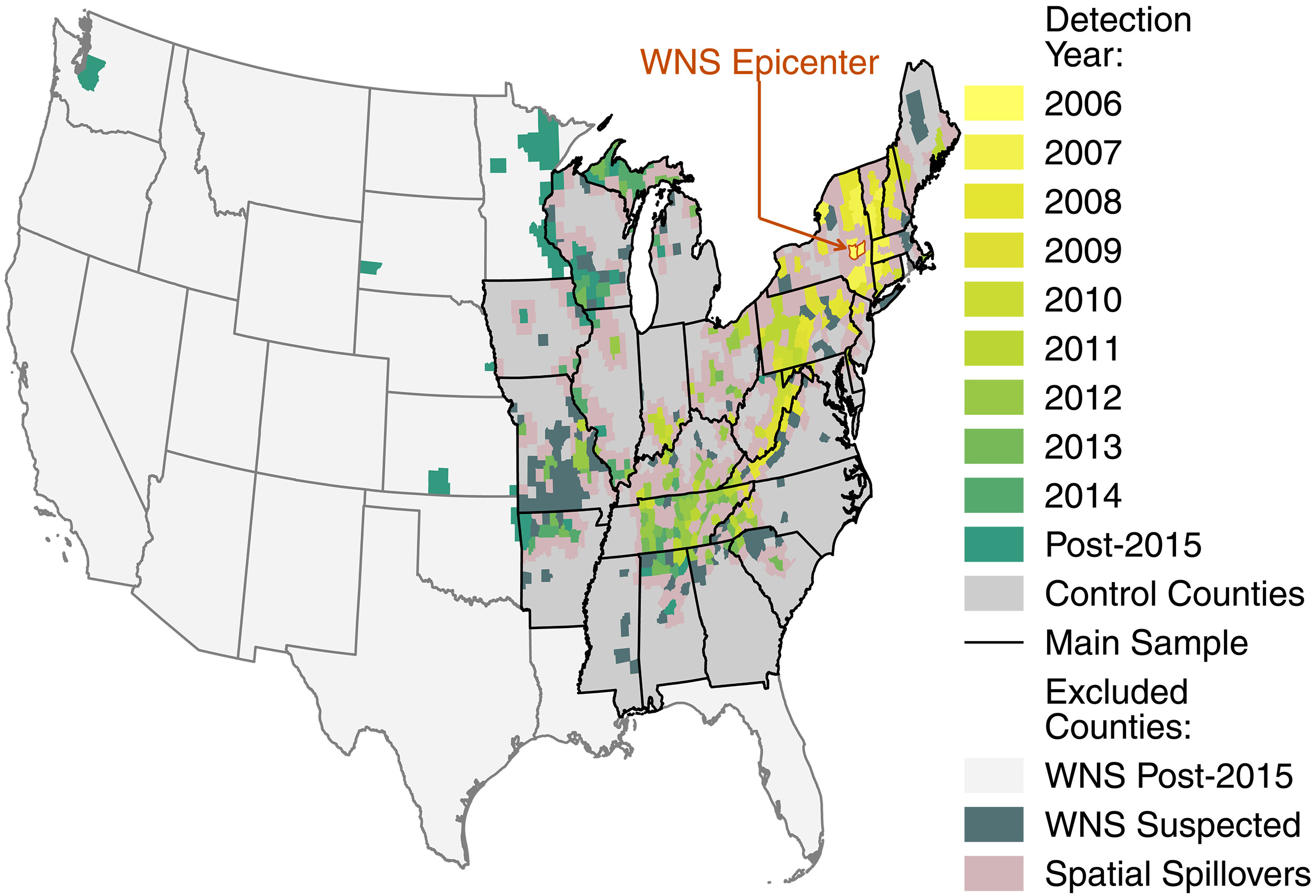

In 2006, individuals discovered bats in New York’s Howe Cave that had a peculiar, fuzzy white substance rising on their snouts.

This was the primary sighting of white-nose syndrome, a fungal illness that has devastated bat populations throughout the US.

Now, a brand new examine has discovered greater than 1,000 human toddler deaths resulted from the lack of bats in North America – which led to elevated pesticide use, a grim reminder of how important this much-maligned mammal is to our wellbeing.

“Bats have gained a nasty popularity as being one thing to worry, particularly after reviews of a potential linkage with the origins [of] COVID-19,” says the examine’s writer Eyal Frank, an ecological economist on the College of Chicago.

“But bats do add value to society in their role as natural pesticides, and this study shows that their decline can be harmful to humans.”

White-nose syndrome (WNS) is attributable to the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which grows across the bats’ mouths, noses, and ears.

Frank used quasi-experimental, observational strategies to discover how, within the wake of a mass die-off of bats as a consequence of WNS, pesticide use elevated together with toddler mortality.

Insect-eating bats hold crop pest numbers in examine, so with bat mortality charges from WNS averaging above 70 p.c within the US for the reason that illness was first detected in 2006, farmers have been pressured to compensate by turning to chemical options to guard crops.

Frank addressed each the financial and well being prices of this shift, evaluating the impacts of pesticide use in counties the place WNS prompted mass bat die-offs, with counties that have been seemingly unaffected.

Counties affected by bat die-offs, he discovered, elevated pesticide use by round 31 p.c. In the meantime, crop gross sales income dropped by practically 29 p.c.

“This demonstrates the substitution between a declining natural input and a human-made input – providing the first empirical validation of a fundamental theoretical prediction in environmental economics,” Frank writes.

He estimates the mixed price to farmers in communities affected by bat die-offs was US$26.9 billion between 2006 and 2017.

And in those self same counties, toddler mortality charges as a consequence of inside causes of demise rose by 8 p.c. That interprets to round 1,334 extra toddler deaths, which Frank exhibits have been seemingly a results of the elevated use of pesticides in WNS-affected counties.

Within the context of the staggered growth of the wildlife illness, Frank discovered these outcomes might be interpreted as causal.

“Any additional alternative explanation would need to change along the expansion path of the wildlife disease around the same timing of its expansion,” he writes.

In extra analyses, he demonstrated that adjustments in crop composition, different mortality varieties, or financial situations couldn’t clarify the noticed outcomes.

“When bats are no longer there to do their job in controlling insects, the costs to society are very large – but the cost of conserving bat populations is likely smaller,” says Frank.

“More broadly, this study shows that wildlife adds value to society, and we need to better understand that value in order to inform policies to protect them.”

This analysis is revealed in Science.