Starting from a threatening hiss to a blood-curdling scream, the sound of the Aztec loss of life whistle is as creepy because the skull-like look of the instrument that produces it.

Mind scans recommend the whistle’s tones might do greater than create a scary atmosphere. Swiss and Norwegian researchers discovered hearing them prompts a wide range of greater order facilities in our brains, suggesting a complexity to the sound that may solely be described as an alarming mixture of the pure and the eerily unfamiliar.

It is no surprise the Aztecs possible used them to reinforce spiritual and sacrificial rituals.

Rumor has it the Mesoamerican civilization additionally used the unnerving sound to strike worry into their foes, throughout warfare, however that has been disputed as no whistles have been discovered at battle websites or in warrior graves.

College of Zurich neuroscientist Sascha Frühholz and colleagues recruited 70 European volunteers for psychoacoustic testing on their private interpretations of a random number of sounds which included tones made by the creepy whistles. The volunteers didn’t have forewarning that cranium whistle sounds could be included, eradicating expectations previous to their scores for every recording.

Thirty-two of the individuals additionally had their brains scanned by fMRI whereas they heard the loss of life whistles amongst a randomized mixture of sounds from 5 totally different classes.

Many of the volunteers likened the whistle to a scream.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

“We present that cranium whistle sounds are predominantly perceived as aversive and scary and as having a hybrid natural-artificial origin,” the staff discovered.

The researchers clarify the unusual combine between pure and synthetic makes it exhausting for our brains to categorize, just like the uncanny valley impact in sound-form. The uncanny valley happens equally, when our brains cannot clearly outline what they’re seeing as pure or synthetic.

Our brains first categorize a sensory enter earlier than utilizing that classification to attribute worth, similar to likeability. However when one thing would not fall inside a transparent class, the paradox leaves us with an unnerving sensation.

Listening to the whistle’s sound activated the low-order auditory cortical areas of the volunteer’s brains – areas which tune into aversive seems like screams or infants crying and direct the mind to research the stimuli on a deeper stage.

“Skull whistle sounds are… rather ambiguous in the determination of their sound origin, which intensifies higher-order brain processing,” the researchers write of their paper.

In comparison with the opposite examined sounds, which included some made by people and animals, some from nature, musical sounds, and sounds made by instruments, the cranium whistle particularly activated the inferior frontal cortex, which offers with elaborate classification processing, and the medial frontal cortex, a area concerned with associative processing.

When all sounds had been in contrast, these made by loss of life whistles had been categorized in their very own group, one near alarm sounds similar to horn, sirens and firearms in addition to close to human noises of worry, ache, anger and unhappy voices.

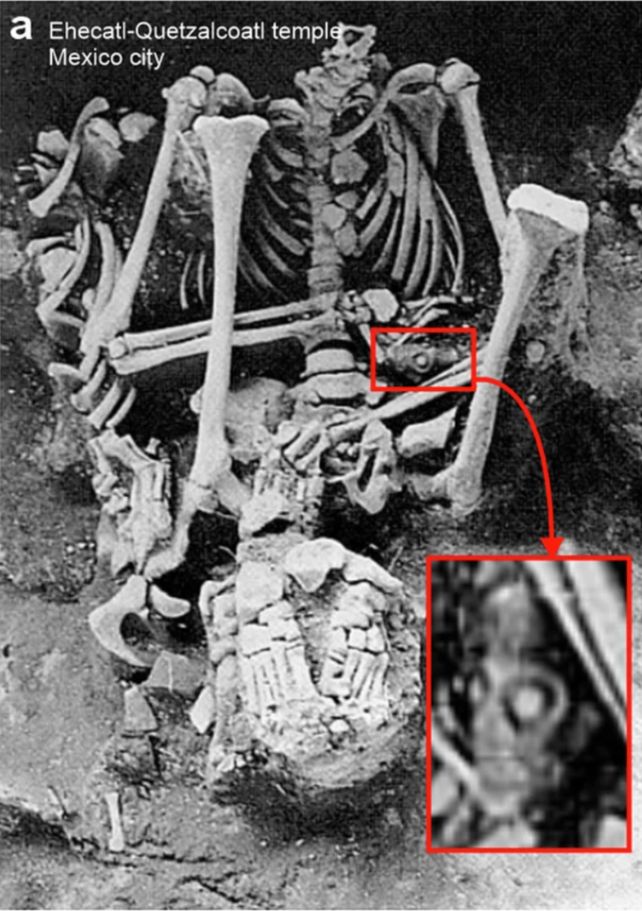

Many variations of those whistles have been present in graves that date again to between 1250 to 1521 CE. A few of them had been related to ritual burials. Given this, and their outcomes, Frühholz and staff suspect the whistles might have been designed to represent Ehecatl, the Aztec God of Wind.

“[Ehecatl] traveled to the underworld to obtain the bones of previous world ages to create humankind,” the researchers clarify.

Alternatively, the spine-chilling cranium whistles might have represented the sharp winds that pierce Mictlan, the Aztec’s underworld.

“Given both the aversive/scary and associative/symbolic sound nature as well as currently known excavation locations at ritual burial sites with human sacrifices, usage in ritual contexts seems very likely, especially in sacrificial rites and ceremonies related to the dead,” Frühholz and staff conclude.

This analysis was printed in Communications Psychology.