A lot of the fossils that we discover in Earth’s crust are preserved in sedimentary rock, the place layers of mineral cowl an organism and, over eons, harden into stone, lifeless beastie impression and all.

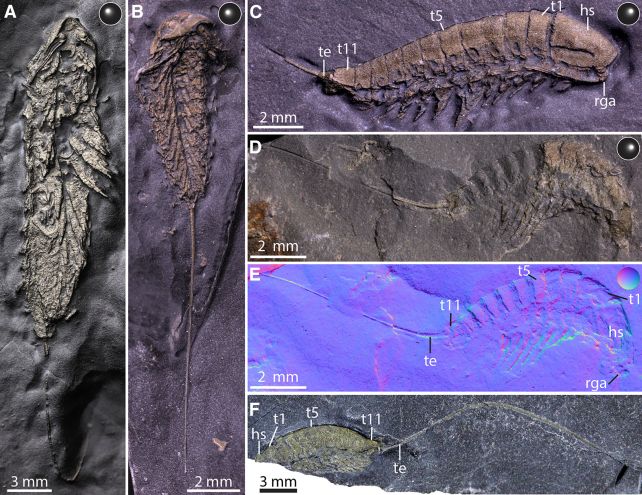

However the beautiful golden fossils found not too long ago in New York State are somewhat completely different. Their tiny our bodies had been slowly changed by a metallic often called iron pyrite, or idiot’s gold, making certain their shapes remained in beautiful situation for 450 million years.

“As well as having their beautiful and striking golden color, these fossils are spectacularly preserved,” says paleobiologist Luke Parry of the College of Oxford within the UK. “They look as if they could just get up and scuttle away.”

Named Lomankus edgecombei, the species represents a completely new marine animal belonging to the Megacheirans — an extinct class of arthropod with massive grabby arms on the entrance of their our bodies for capturing their prey.

Fossilization might be fairly tough on the unique materials. Processes usually topic the stays to stress, warmth, or a mixture of each, leading to important alteration of the anatomy that makes it troublesome to see its options clearly, or in three dimensions.

A fossil mattress that preserves organisms in exquisitely advantageous element is named a Lagerstätte – and a Lagerstätte often called Beecher’s Trilobite Mattress is phenomenal even amongst this class. Though it is just some centimeters thick, it comprises the fossils of a variety of historic trilobites whose our bodies have turned to idiot’s gold.

That is the place Parry and his colleagues discovered L.edgecombei.

“Pyrite forms today through the action of sulfate-reducing bacteria that break down organic material in the absence of oxygen and produce hydrogen sulfide,” Parry instructed ScienceAlert.

“This can then react with iron to form pyrite, which is iron sulfide. So, to form pyrite you need organic material, iron, and a lack of oxygen. The sediments that contain the fossils are low in organic material but high in iron and so the carcasses of the animals preserved there are like small islands where the conditions for pyrite to form are just right.”

The animals had been doubtless buried alive in big dumps of sediment carried by occasions referred to as turbidity currents, creating a really particular set of circumstances that allowed the arthropods to be pyritized from the skin in.

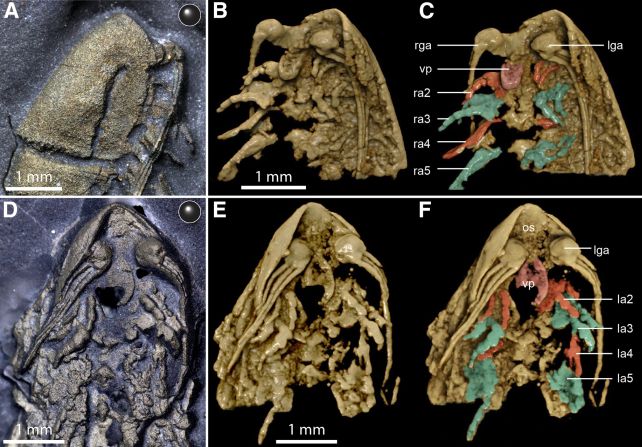

The result’s a set of L. edgecombei fossils which are exceptionally properly preserved in three dimensions, giving us new perception into the anatomy of Megacheirans. And these little guys are significantly thrilling, as a result of they lived in a time when the Megacheirans had been on the decline. This class of critters was ample and numerous throughout the Cambrian, between 541 and 485 million years in the past, however had been largely extinct by the early Ordovician interval that adopted, between 485 and 443 million years in the past.

This implies L. edgecombei was one of many final surviving Megacheiran species on Earth, and its anatomy provides some insights into how the appendages on the heads of arthropods become the antennae, pincers, and fangs seen on bugs, crustaceans, and arachnids right now.

“Today, there are more species of arthropod than any other group of animals on Earth,” Parry says. “Part of the key to this success is their highly adaptable head and its appendages, that have adapted to various challenges like a biological Swiss army knife.”

The fossils reveal that the grabby arms seen on different Megacheirans, often called ‘nice appendages’, shrank and adjusted form for L. edgecombei, suggesting a change in operate. The claw used for grabbing in different species is far smaller; in the meantime, three lengthy, whip-like appendages often called flagellae are for much longer.

Since L. edgecombei had no eyes, this transformation means that the creatures used their nice appendages for sensing greater than prey-snatching.

“Rather than representing a ‘dead end’,” Parry defined, “Lomankus shows us that megacheirans continued to diversify and evolve long after the Cambrian, with the formerly fearsome great appendage now performing a totally different function.”

The analysis has been printed in Present Biology.